Why the Conformon Model Does Not Reject Chemiosmosis — and Why This Matters for the Future of Bioenergetics

Clarifying a Fundamental Misunderstanding in the Global Oxidative Phosphorylation Debate

Sungchul Ji, Ph.D.

Emeritus Professor of Theoretical Cell Biology, Rutgers University

1. Introduction: A Persistent Misunderstanding

A colleague of mine recently wrote the following critique of the conformon model of oxidative phosphorylation (oxphos):

“The problem is discounting chemiosmosis, when it has given rise to both proton and electron transport.”

This statement reflects a very common misunderstanding in biochemistry.

The conformon model which was introduced in 1974 [1]—does not discount chemiosmosis [2].

It does not even compete with it in the way many assume.

Instead:

The conformon model [1] subsumes the chemiosmotic model [2].

It incorporates proton gradients as one of two essential paths for ATP synthesis.

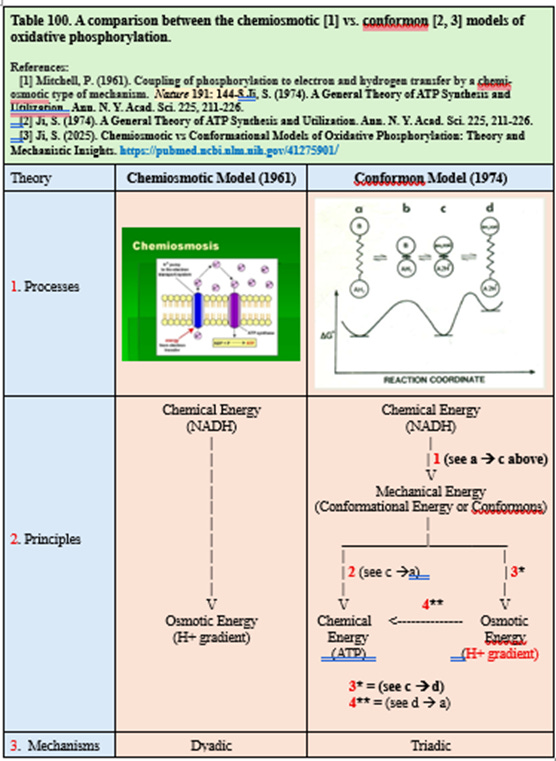

Table 100 below makes this explicit:

Chemiosmosis = a dyadic mechanism (chemical → osmotic) (see the first column, Table 100)

Conformon = a triadic mechanism (chemical → mechanical → chemical + osmotic) (see the second column, Table 100)

The conformon model preserves everything chemiosmosis correctly explains—and adds the missing mechanistic step:

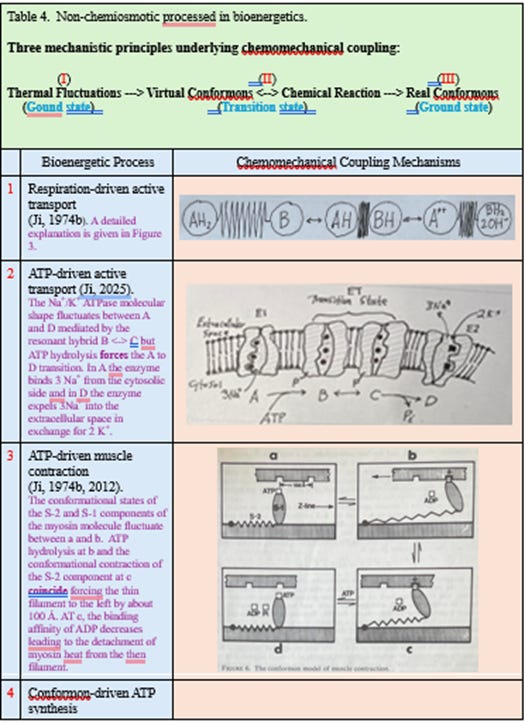

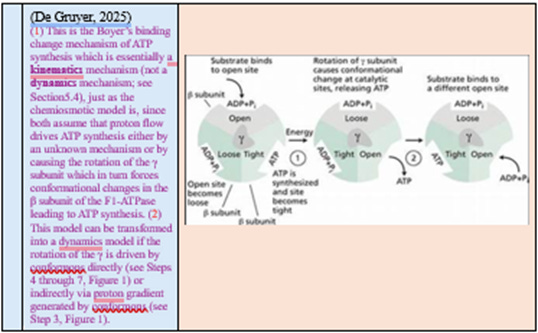

conformational energy packets stored in proteins (“conformons”) that directly drive ATP synthesis by driving the rotation of the γ subunit of the F1 ATP synthase [3] (see Row 4, Table 4).

The misunderstanding arises because many assume that adding a new mechanism implies rejecting the old.

But biology is rarely dyadic; it is triadic.

2. Chemiosmosis: A Brilliant Discovery — But an Incomplete Mechanism

Peter Mitchell’s (1961) chemiosmotic hypothesis [2] deserved its Nobel Prize.

It revolutionized bioenergetics by showing that:

Electron transport generates a proton gradient (see first column, Table 100 below).

The proton-motive force (PMF) drives ATP synthesis [2a]

However, Mitchell never identified how PMF causes mechanical rotation or conformational changes within ATP synthase. The “binding change mechanism” (Boyer & Walker) [4] filled part of this gap, but still lacked a microscopic physical driver.

Chemiosmosis gave us the what.

It never gave us the full how.

Chemiosmosis correctly identified proton gradients as a genuine and indispensable component of cellular energetics [2]. Proton gradients are measurable, regulatable, and tightly coupled to metabolism. No serious alternative denies their existence.

However, proton gradients are scalar fields. They are delocalized and statistical in nature. As such, they cannot by themselves explain several defining features of biological work:

ATP synthesis occurs in discrete steps, not continuously (see Panel (D) of Figure 2 in [11]).

Energy conversion is directional, not merely downhill

Molecular machines exhibit memory and hysteresis

Fast electronic events are tightly coordinated with slow conformational changes [18]

These properties are characteristic of machines, not fields.

Thus, while chemiosmosis explains where energy comes from, it does not explain how that energy is organized into controlled molecular work.

Torsion is energy stored as elastic rotational strain distributed along a structured system. At the molecular level, torsion resides in:

· dihedral angles of polymer backbones

· helical protein and nucleic-acid structures

· elastic twisting of shaft-like elements in molecular machines

Unlike gradients, torsional energy is:

· localized yet distributed

· reversibly stored

· intrinsically directional

· releasable in discrete steps

In short, torsion has exactly the properties required of biological energy.

What the conformon model implicitly described is now made explicit:

A conformon is a localized packet of stored torsional energy.

3. The Conformon Model: Completing the Mechanistic Picture

In 1974, David E. Green (1910-1983) and I proposed that biopolymers store and transmit quantized packets of mechanical energy—conformons—analogous to phonons in condensed matter physics [1, 5]..

A conformon [5].is:

“A conformational energy packet stored in sequence-specific sites within a biopolymer that drives mechanical motions essential for biological work.”

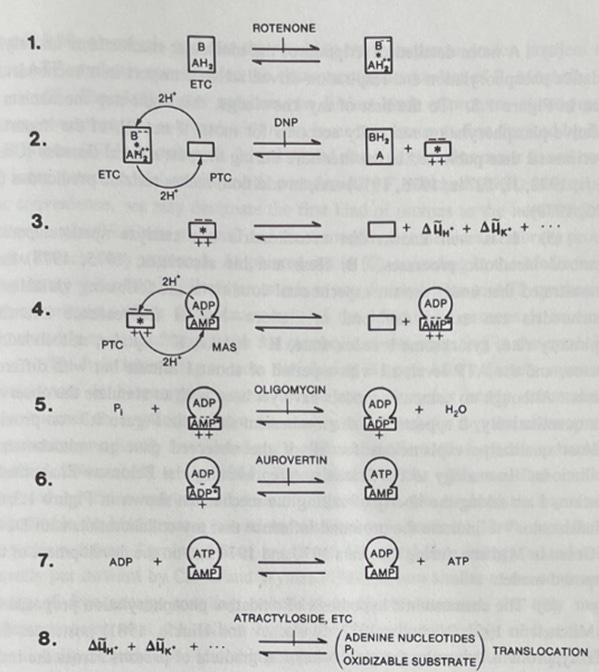

In oxidative phosphorylation, conformons (symbolized by *):

Are generated during electron/chemical energy dissipation (see Step 1, Figure 10 below)

Drive the conformational changes in ATP synthase required for ATP formation (see Steps 4, 5, and 6 in Figure 10)

Also help generate proton gradients (chemiosmosis) as a secondary mechanism (see Step 3, Figure 20).

This yields two ATP-synthesis pathways:

Path 1: Direct Conformon-Driven ATP Synthesis (see Steps 1 and 2 in Table 100).

Aerobic tissues (e.g., heart, brain) rely heavily on this rapid, efficient mechanism.

Path 2: Indirect Chemiosmotic ATP Synthesis (see Steps 1, 3* and 4**, Table 100).

Proton gradients serve as an energy buffer, enabling ATP synthesis even when oxygen is scarce.

This dual mechanism predicts that:

Proton gradients should be especially important in anaerobic organisms

PMF should prolong life in ischemic tissues when electron flow is impaired

Both predictions match known physiology.

Thus chemiosmosis is not rejected—

it is contextualized and explained.

ATP synthase is often described metaphorically as a turbine driven by proton flow. This image is misleading. Proton translocation does not directly produce ATP. Instead, it loads torsional strain into elastic protein elements of the enzyme. The catalytic synthesis of ATP occurs when this stored torsional energy is released in a controlled, stepwise manner at the active sites.

In this integrated view:

Chemiosmosis loads the spring

Torsion stores the energy

Conformational transitions release the energy

This explains why ATP synthesis is quantized, why rotation occurs in steps, and why energy can be partitioned between ATP production and maintenance of the proton-motive force.

Chemiosmosis is therefore not wrong — it is incomplete.

4. Resolving a False Disjunction

The long-standing debate between chemiosmosis and conformons reflects a classic false disjunction bias:

either gradients do the work

or conformations do the work

The correct formulation is triadic:

Gradients prepare the system → torsion stores the energy → conformational change performs the work

Once torsion is introduced, the apparent opposition dissolves.

Chemiosmosis becomes a thermodynamic biasing mechanism embedded within a torsion-based mechanochemical system.

5. JPDE and Evolution in Torsional Space

Ji’s Principle of Dynamic Equilibrium (JPDE) describes how information arises through selection from a field of possibilities (see Step (V) of Figure 2 in [22]). At the molecular level, those possibilities are torsional configurations.

Proteins explore a vast torsional configuration space. Environmental constraints—pH, redox state, ligand binding, hydration—select specific torsional states. These selected states store both energy and information.

Evolution, in this view, operates not merely on sequences, but on torsional motifs stabilized by the environment.

Recognizing torsion as a fundamental biological energy variable:

completes the conformon model

resolves the chemiosmosis debate without rejecting gradients

explains stepwise molecular control

grounds information generation in physical selection

aligns bioenergetics with geometry, not metaphor

Most importantly, it restores mechanical intelligibility to life. Life does not run on gradients alone. Gradients bias processes, but torsion executes decisions. Energy in biology is not merely stored as differences in potential, but as twisting encoded in molecular geometry, selected by the environment and released with precision (see Figure 2 in [22]).

Biology is the science of how torsional energy becomes function.

6. Why Chemiosmosis Remains Essential in the Conformon Framework.

Table 100 below shows this clearly.

Chemiosmosis appears twice in the conformon column:

As an outcome of conformon dynamics (mechanical → osmotic) (see a --> d, Table 100).

As a parallel pathway for ATP synthesis (osmotic → chemical) (see Steps d --> c --> a, Table 100).

This makes chemiosmosis:

A necessary component of oxphos

But not a sufficient explanation by itself

In other words,

The conformon model explains chemiosmosis; it does not replace it.

7. Why the Misunderstanding Persisted for 50 Years

There are three reasons:

1. A “false disjunction bias”

Many scientists assume:

“Either chemiosmosis is right, or conformons are right.”

But this is a false disjunction. Biology is rarely an “either/or” system. It is almost always both/and—a triadic integration.[6]

2. Lack of mechanistic language in classical biochemistry

Conformons emerged from biophysical chemistry and quantum mechanics [7], not from classical enzymology [8].

The idea of “quantized mechanical energy packets” felt foreign to biochemists.

3. The dominance of electron microscopy and structural biology

These fields favored static pictures rather than dynamic energy flows.

But as cryo-EM [9] and single-molecule biophysics [10, 11] have matured, the mechanical framework now appears unavoidable.

8. Unified View: Dyadic vs. Triadic Mechanisms

Table 101 identifies the key conceptual divide:

A dyadic model cannot explain ATP synthase’s rotary catalysis [12] (see Row 4, Table 4)

A triadic model can (see Row 4, Table 4).

This unity is essential as oxphos undergoes its long-overdue paradigm shift—reflected in the recent BioSystems Special Issue on Oxidative Phosphorylation [1].

9. Summary

Figure 10. The conformon model of the mitochondrial structure and function [3].

Misunderstandings about scientific theories often persist not because the theories are flawed, but because they are ahead of their time.

The conformon model anticipated:

protein dynamics as information carriers

mechanochemical coupling in enzymes [1] (see Row 1, Table 4 above)

triadic architectures in biological systems [6]

the shift from static structures to dynamic processes [16]

All of these are now central themes in modern biophysics [15].

It is time to retire the false dichotomy between chemiosmosis and conformons.

The biochemical community can progress only by embracing a unified energy-transduction framework—one that respects Mitchell’s monumental discovery while completing it with the deeper mechanistic insights of conformon dynamics [15].

10.Closing Reflection: What Biochemists Need to Understand Now

1. Chemiosmosis is not rejected by the conformon model.

It is embedded within it.

2. Conformons provide the missing mechanistic step needed to explain ATP synthase rotation and energy coupling.

3. Chemiosmosis plays a critical role in:

Anaerobic metabolism

Survival during ischemia

Buffering mechanical energy into a proton reservoir

Communication between mitochondria and the cytosol so that mitochondria synthesize ATP only when needed in the cytosol.

4. The conformon model is triadic and integrative—

precisely the kind of architecture biological systems exhibit [6].

5. The future of bioenergetics will require integrating:

Chemical energy

Mechanical (conformational) energy

Osmotic energy

Rather than debating “chemiosmosis vs conformons,” the proper question is:

How do chemiosmosis and conformons cooperate to orchestrate the symphony of oxidative phosphorylation as depicted in Figure 10?

Misunderstandings about scientific theories often persist not because the theories are flawed, but because they are ahead of their time.

The conformon model anticipated:

protein dynamics as information carriers [5]

mechanochemical coupling in enzymes [13]

triadic architectures in biological systems [6]

the shift from static structures to dynamic processes [16References:]

All of these are now central themes in modern biophysics [15].

It is time to retire the false dichotomy between chemiosmosis and conformons.

The biochemical community can progress only by embracing a unified energy-transduction framework—one that respects Mitchell’s monumental discovery while completing it with the deeper mechanistic insights of conformon dynamics.

References:

[1] Ji, S. (1979). The Principles of Ligand-Protein Interactions and their Application to the Mechanism of Oxidative Phosphorylation, in Structure and Function of Biomembranes, K. Yagi (ed.), Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo, pp. 25-37.

[2] Chemiosmosis. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemiosmosis

[2a] Jagendorf, A. T., & Uribe, E. (1966). ATP formation caused by acid–base transition of spinach chloroplasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 55: 170–177.

[3] Vlasov, A.V. (2022). ATP synthase FOF1 structure, function, and structure-based drug design. Cell Mol Life Sci. 79(3):179. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04153-0

[4] Boyer, P. (1997). Binding Change Mechanism. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1997/boyer/25946-the-binding-change-mechanism/

[5] Conformon. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conformon

[6] Ji, S. (2018). The Universality of Triadic Relation (ITR). In: The Cell Language Theory: Connecting Mind and Matter. World Scientific Publishing, New Jersey.

[7] Ji, S. (2012). The Kinetics of Ligand-Protein Interactions: The“Pre-fit” Mechanism Based on the Generalized Franck-Condon Principle. In: Molecular Theory of the Living Cell: Concepts, Molecular Mechanisms, and Biomedical Applications. Springer, New York. Pp. 209-214.

[8] Koshland, D. E., Jr. (1958). Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 44, 98-104.

[9 ]Cryogenic electron microscopy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryogenic_electron_microscopy

[10] Molecular biophysics. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Molecular_biophysics

[10a] Ishii, Y. and Yangida, T. (2000). Single Molecule Detection in Life Science, Single Mol. 1(1), 5-16.

[11] Ishijima, A., Kojima, H., Higuchi, H., Harada, Y., Funatsu, T. and Yanagida, T. (1998). Simultaneous measurement of chemical and mechanical reaction, Cell 70, 161-171.

[12] Ji, S. (2018). Rochester-Noji-Helsinki (RoNoH) model of oxphos. In: The Cell Language Theory: Connecting Mind and Matter. World Scientific Publishing Europe Ltd., London. P. 129.

[13] Xie, P. (2021). Insight into the chemomechanical coupling mechanism of kinesin molecular motors. Commun. Theor. Phys. 73 057601DOI 10.1088/1572-9494/abecd8

[14] Dissipative Structures. https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/dissipative-structures

[15] Wray, V., Witkov, C., and Andresen, B. (2025). Toward the Unified Theory of ATP Synthesis/Hydrolysis: Integrating Physics, Chemistry , and Biology. https://www.sciencedirect.com/special-issue/10VK46MFTR8

[16] Prigogine, I. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilya_Prigogine

[17] Nath, S. (2017). Two-ion theory of energy coupling in ATP synthesis rectifies a fundamental flaw in the governing equations of the chemiosmotic theory. Biophys. Chem. 230: 45-52

[18] Ji, S. (2026). Chemiosmotic vs conformational models of oxidative phosphorylation: Theory and mechanistic insight. BioSystems 259 (2026) 105637.

[19] Torsion (mechanics). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torsion_(mechanics)

[20] Green, D.E. and Ji, S. (1972). Electromechanochemical Model of Mitochondrial Structure and Function. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (U.S.) 69, 726 729.

[21] Type-token distinction. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type%E2%80%93token_distinction

[22] Ji, S. (2025). Geometry of Reality. https://622622.substack.com/p/geometry-of-reality

_______________________________________________________________________________